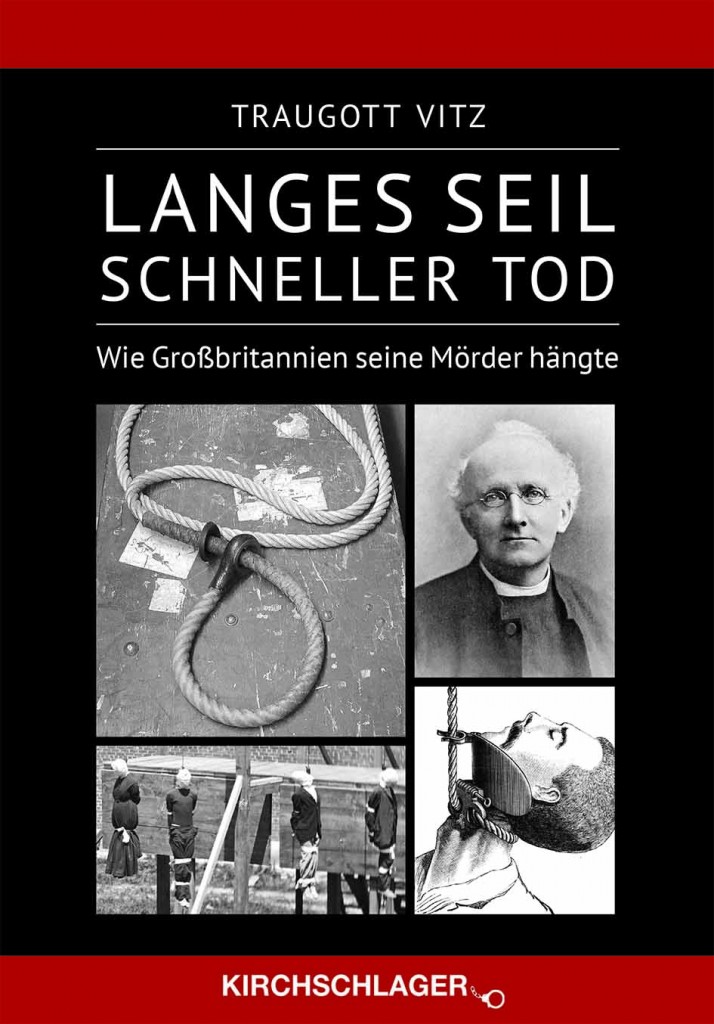

Von allen Hinrichtungsarten ist wohl keine so britisch wie das Hängen. Die Briten exportierten sie überall dort hin, wo sie als Kolonial- oder Besatzungsmacht das Sagen hatten: Nach Nordamerika, Australien, Neuseeland, Indien, Singapur, Palästina… Bis 1868 hängten die Briten öffentlich. Bis 1964 hängten sie hinter Gefängnismauern. Sie machten eine Wissenschaft daraus – oder versuchten es wenigstens. Sie waren stolz darauf – und hielten alles, was damit zusammenhing, rigoros geheim. Inzwischen aber sind die meisten Akten zugänglich. Aus Material des Britischen Nationalarchivs, Zeitungsberichten des 19. Jahrhunderts und Biographien der Henker hat Traugott Vitz die Geschichte der letzten 96 Jahre britischer Hinrichtungspraxis geschrieben.

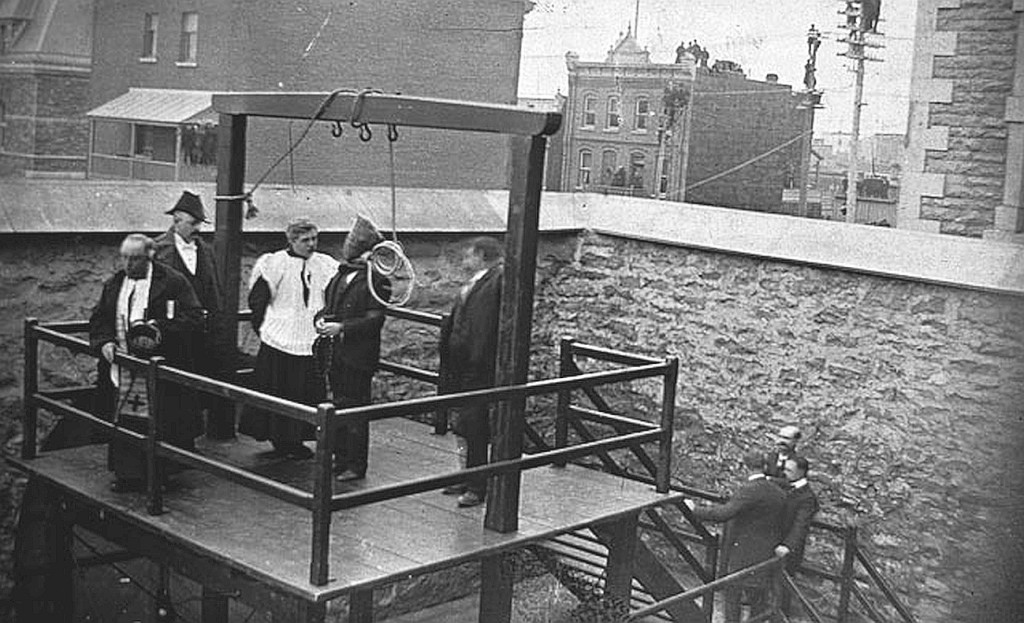

Der kanadische Henker John Radclive (ganz rechts) behauptete fälschlich, ein Schüler des englischen Henkers William Marwood zu sein.

Canadian hangman John Radclive (far right) falsely claimed to be a pupil of the English executioner William Marwood.

Britisches Hängen war angeblich schnell, human und schmerzlos, aber stimmte das? Nun: beinahe. Allerdings sicher nicht von Anfang an, als ein viktorianischer Universalgelehrter zum ersten Mal eine Formel entwarf, die die Fallhöhe zum Körpergewicht in ein Verhältnis setzte. Entlang von Zeitungsberichten und Archivmaterial des 19. Jahrhunderts folgt Traugott Vitz den Spuren von William Marwood (dem ersten englischen Henker, der den langen Fall verwandte), den Erfolgen und Fehlschlägen seines Nachfolgers James Berry, den sorgfältigen Nachforschungen des Todesstrafen-Komitees (1886-88), den Zeiten der Henkerdynastien Billington und Pierrepoint bis zu den letzten englischen Hinrichtungen im Jahr 1964. Zum ersten Mal wird der entscheidende Einfluß des Gefängnisarztes James Barr (später Präsident der British Medical Association) auf die Entwicklung der Abläufe und der Fallhöhentabelle aufgezeigt. Als deutscher Autor und weil er das Thema als erster auf deutsch behandelt, befaßt sich Vitz etwas ausführlicher mit den von Albert Pierrepoint vorgenommenen Hinrichtungen von Kriegsverbrechern in Hameln (Deutschland). Er erzählt in sehr lesbarer, lebhafter Weise, aber vor einem beeindruckenden Hintergrund an Quellen, der medizinische Lehrbücher und Zeitschriften einschließt.

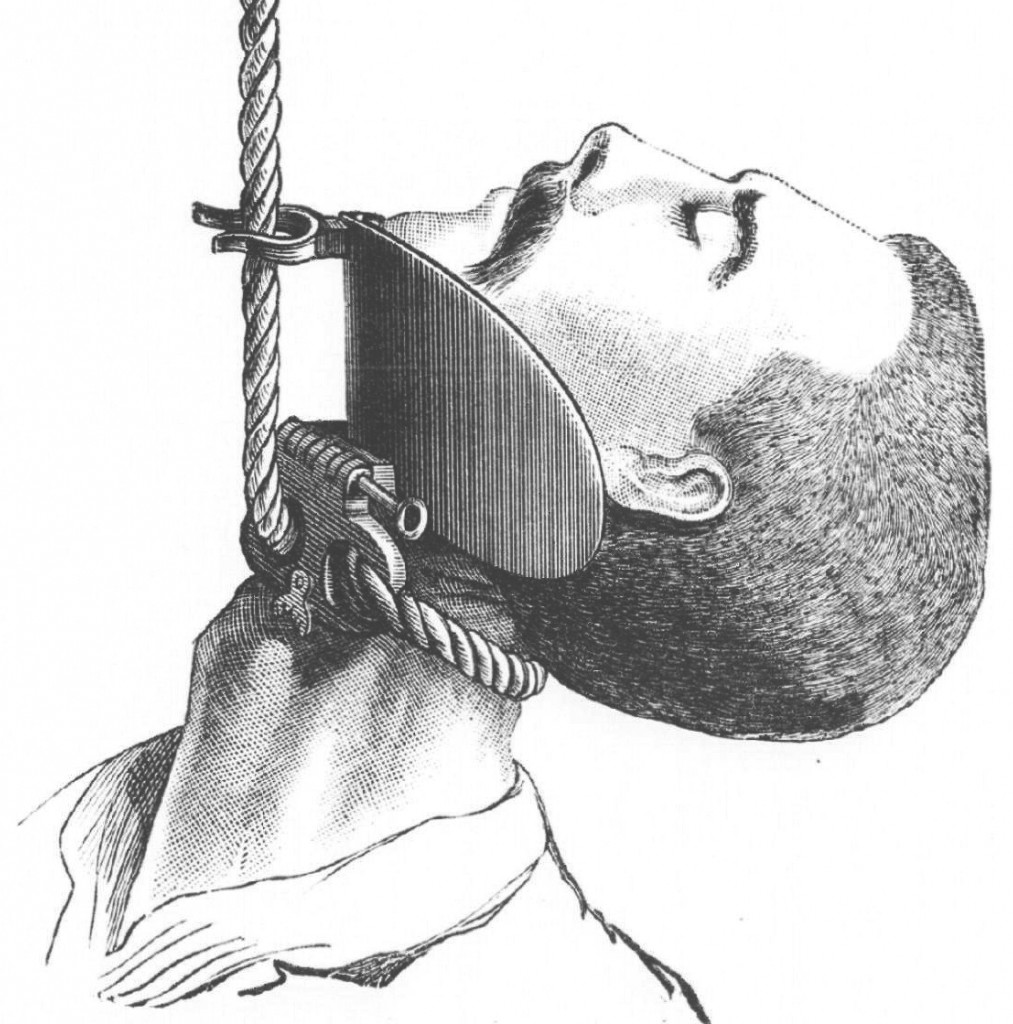

Die „Kinnmulde“ des britischen Chirurgen Dr. Marshall – eine exzentrische Erfindung, die in der Praxis nie benutzt wurde.

„Chin Trough“ designed by British surgeon Dr. Marshall – an excentric invention which never saw actual use.

Softcover, Franz. Broschur, 272 Seiten, zahlreiche s/w Abbildungen, Preis: 14,95 Euro

Softcover, Franz. Broschur, 272 Seiten, zahlreiche s/w Abbildungen, Preis: 14,95 Euro

British Hanging was said to be swift, humane, and painless, but was it? Well, almost: certainly not from the beginning, when a Victorian polymath came up with the first formula relating drop length to body weight. Using British 19th century newspapers and archive documents, Traugott Vitz traces the steps of William Marwood (the first English hangman to use the long drop), the successes and mishaps of his successor James Berry, the diligent investigations of the Capital Sentences Committee (1886-88), and follows the times of the hangman dynasties of the Billingtons and the Pierrepoints to the last English executions in 1964. For the first time, the crucial influence of prison doctor James Barr (later to become president of the British Medical Association) in developing procedures and drop tables is shown. As a German author and covering the subject in German for the first time, Vitz deals in some detail with the executions of war criminals done by Albert Pierrepoint at Hameln (Germany). He tells his tale in very readable, vivid language but from an impressive background of sources, including medical textbooks and journals.

Long Rope, Quick Death

How Britain Hanged Her Murderers

Foreword

Motto

From the Beginnings up to William Marwood’s Death

page 9: Origin of hanging in Britain. The course of a criminal trial.

page 12: How executions were performed in the beginning, then at Tyburn, then at Newgate in front of the Debtor’s Door. What the Sheriff had to do with them.

page 19: William Calcraft’s way of hanging people. What it looked like for the onlookers. Subject of this book: The last 96 years of hanging in Britain. The steps of abolition.

page 22: State of things in 1868: Calcraft’s method. What the gallows looked like. The “procession” to the gallows. Two articles by Charles Croker King in the Dublin Quarterly Journal of Medical Science (1854 and 1863). Hanging of 38 Indians in Mankato (1862). Hanging of the Lincoln Assassins and of Henry Wirz (1865).

page 29: Samuel Haughton’s article On Hanging (1866). Execution of Andrew Carr (1870; decapitation).

page 35: William Marwood. Personal background. Where did he put his knot? What were his drop lengths?

page 39: Samuel Haughton’s Animal Mechanics (1873) and his address to the Surgical Society at Dublin (1875). What Marwood knew or did not know about Haughton.

page 41: Calcraft’s dismissal and Marwood’s beginnings. Executioners and their alcohol consumption.

page 43: How the public felt about felons ‘dying hard’. The Maamtrasna Murderers’ execution. Myles Joyce. James Burton. The use of pack thread for tying the excess rope overhead, the use of planks over the trap door.

Conclusion: Perhaps it is not safe to say Marwood “invented” the long drop, but he certainly introduced it into England, and his was the invention of the metal thimble and the leather washer.

Digression: Bartholomew Binns

page 53: The selection process for Marwood’s successor. Binns had no previous experience. The execution of Henry Dutton (3rd December 1883, Liverpool). Dr. James Barr. Executions of Patrick O’Donnell (Newgate), Flanagan and Higgins (Liverpool) and M’Lean (Liverpool). Summary of inquest findings. Binns dismissed by the London aldermen and sheriffs.

Trial and Error – and then a Committee

page 61: James Barr’s 1884 article in The Lancet. James Berry being selected for the execution of two poachers at Edinburgh. Berry’s book My Experiences etc. His equipment and methods. His first drop table (which he does not seem to have followed closely). The cases of Joseph Lowson, Thomas Harris, Ernest Ewerstadt, and Arthur Shaw.

page 72: The year 1885: John Lee (Exeter), Moses Shrimpton (Worcester), and Robert Goodale (Norwich, decapitation). Reaction in the newspapers. The Capital Sentences Committee.

page 80: The work of the committee. The evidence of Samuel Haughton and Leonard Ward. The drop tables of Leonard Ward and James Berry: almost identical. James Berry lies to the committee: He did not follow Ward’s table “closely”. What Ward’s table would have looked like if brought into the form as used later (p. 87).

page 87: Dr. Marshall’s evidence. His invention of a “chin trough”. The committee’s rejection of same. Committee report printed probably in July 1888. Dr. Marshall’s reaction: His article in the British Medical Journal. Ensuing “War of Letters” with James Barr. Chin Trough actually tested ONCE: Report of Wood Jones (1931).

page 93: The Home Office drawings for a gallows (1885). Drop table of the Committee Report (1888). The “Government Rope”. The committee’s recommendations with regard to rope length. How to avoid a loss of drop energy. The split beam and the adjustable brackets. A recommendation which was NOT followed: risk decapitation rather than strangling.

The Home Office Reluctantly Takes the Reins

page 101: The Home Office has no control over the executioners nor over the sheriffs. It can only make suggestions and offers. Should executioners be recruited from the Prison Service? The committee would rather have assistants who over time acquire experience. The Home Secretary’s pledge (in the Commons) to try and find suitable persons and to offer them to the sheriffs for employment. His own servants delay the plan for months. Dr. Barr is asked to train the candidates. The first “list of suitable persons”, the Memorandum to Sheriffs and the Memorandum of Instructions for Carrying out the Details of an Execution.

page 112: Berry’s so-called “resignation” – a publicity stunt. Execution of John Conway, and Berry’s run-in with Dr. Barr. The Memorandum to Sheriffs, verbatim. The Memorandum of Instructions, verbatim, with commentary.

Digression: Hanging in Australia and Canada

page 131: The drop table of the Capital Sentences Committee (1.260 ft-lbs) never officially sanctioned. Drop table of April 1892 (840 ft-lbs) never followed by the executioners.

page 134: The “Particulars of Executions” (Melbourne). The knots and nooses used in Australia. The gallows at Melbourne.

page 139: Canada. John Robert Radclive (not a pupil of Marwood!). His technique.

The Home Office Establishes Best Practice

page 143: John Billington starts using his sons as assistants. William Billington performs an execution without previous practice. James Billington starts to worry his superiors with his “intemperance”. The Home Office agrees to organize training courses for new assistants (1900). How training courses went in 1901, 1932, 1940, 1948, and 1960.

page 150: Albert Pierrepoint’s training. Respites granted because of “physical abnormities”. Heavy culprits. Which drop energy the executioners actually used 1892-1913.

page 155: Wood Jones: “The ideal lesion…” (1913). De Zouche Marshall, “Judicial Hanging” (1913). The new drop table of October 1913. The addition of 9 inches in 1939. The building of Execution Suites. The Wandsworth Suite, and how a hanging took place there. Nine to twelve, maximum 35 seconds from entrance of executioner to drop.

Digression: The Role of the Prison Chaplain

page 169: A Liturgy for the Use at an Execution (1897 to 1927). Previously: The Burial Liturgy, but not all of it. Chaplains going into the execution chamber. Example: Rev. Blakemore / execution of S. Dougal (1903). Liturgy proves to be too long as course of action accelerates. 1939: Chaplain should stand at the door of the execution chamber. What the chaplain had to do after the execution: Sign certificate, perform burial. Bodies buried in the prison yard three deep.

The Executioner at War:

Soldiers, Spies, and Traitors

page 175: The Treason Act (1351). The Treachery Act (1940). Parliamentary debate of it. Josef Jakobs – sentenced to be shot under the Treachery Act. Karel Richard Richter – the man who fought his executioners for 17 minutes. The cock-and-bull stories Jackson and Purchase told about Richter’s hanging and about elongated necks.

page 182: Hangings at Shepton Mallet under the “United States of America (Visiting Forces) Act 1942”.

page 183: Hangings of five German prisoners of war for the murder of Sergeant Major Wolfgang Rosterg. The story behind it: Planned outbreak from Devizes PoW camp.

page 188: Hanging of two more German PoWs for the murder of Sergeant Gerhart Rettig, falsely believed to have given away an outbreak plan.

page 188: Albert Pierrepoint as executioner of German war criminals, D.P.s and British soldiers at Hameln. Where the Hameln gallows was.

page 193: Pierrepoint’s assistants at Hameln. Hangings of 13 Dec 1945. Medical experiments under the direction of Dr. Buckland. Chloroform injections used. How electrocardiographic readings of hanged men were obtained. Pierrepoint’s trip to Austria, hanging eight men and training Austrians in the British method.

page 199: The Nuremberg hangings performed by John C. Woods. New research about his antecedent, revealing a big bunch of lies.

page 201: The trials and executions of William Joyce and John Amery.

Malpractice and Political Head Wind

page 209: What was done to keep execution details hidden from public view: (1) Secrecy. No journalists after 1934. Executioners signing secrecy bonds. Official Secrets Act. Governors and surgeons advised by Home Office on wording of inquest evidence.

page 212: (2) Careful selection of new executioners. Examples of C.E. Green and H. Durling. Police of home town report on criminal record, if any, and general character. Training course, test, acting as “second assistant” (after 1929). The performance questions on the LPC4 sheet. Executioners under scrutiny: T.W.Pierrepoint, H. Pierrepoint’s dismissal, William Willis’ dismissal, T.M. Phillips’ request of more alcohol, Herbert Morris’ insubordination, R.O. Baxter’s reduced eyesight, Albert Allen’s drop into the pit, similar incidents in 1896 and 1953, Baxter dismissed because of failing eyesight, Allen dismissed for incorrect application of the noose, Syd Dernley dismissed because of his prison sentence.

Resignations of John Ellis, Albert Pierrepoint, Lionel Mann. Psychological damage: H.W. Critchell and G. Dickinson.

page 220: (3) Quality management with regard to equipment.

page 221: Mishaps. Execution of Goldthorpe (noose not drawn tight). Unnamed man coming to life after being taken off the rope too early in 1959. Similar cases reported in 1927 and 2006.

page 224: Development of medical knowledge about hanging. Kinkead 1885, Barr 1884, Haughton 1873. Heart beating after hanging: sphygmographic recordings. Is there a significant heartbeat proving insensibility? (Haughton, Carte). Littleton 1893. Wood Jones 1913. James/Nasmyth-Jones 1992. Long drop hanging with submental knot does NOT regularly result in a fracture of a vertebra. It breaks the ligaments between the vertebrae and tears the spinal cord.

page 232: Medical literature sometimes sloppy in facts. Example: Five factual errors within three sentences (Hermann/Saternus, 2007).

page 234: Spence et al. 1999, Wallace et al. 1994. Neurological theories.

page 237: Opponents to Capital punishment. Violet Van der Elst. Her biography, her actions 1935ff.

page 244: Sydney Silverman M.P. Three cases: Evans, Bentley, Ellis. Steps towards abolition. Availability of capital punishment without impact on murder rate: Statistics 2011 for Germany, UK, USA.

Conclusion

page 251: No executioner can guarantee that he will always cause a fracture-dislocation C2/3. And even if he could, we don’t know how fast the culprit will loose consciousness – in seconds or in fractions of a second? So – if the death penalty must exist, hanging would not be the method of my choice.

But must it exist? Personal answer as a protestant Christian, theologian and post-war German: No. We can and should do without it.

Bibliography (page 255 ff)

Annotations (page 259 ff

Image Credits (page 268)

Author’s Image & Bio (page 271)